Of all the new technologies appearing on the farm, “remote sensing” systems (devices that measure conditions from a distance, commonly an aircraft or satellite) are unique in their ability to deliver information on the existing conditions in the field.

The Value of Remote Sensing Data in Agriculture (Part I)

The Value of Remote Sensing Data in Agriculture (Part I)

Michael Ritter | SLANTRANGE

Reprinted with permission from SLANTRANGE:

Part I: What is Data Value?

There’s a lot of talk about data lately. “Ag data”, “personal data”, “big data”, “data analytics”, “artificial intelligence”, “machine learning”, “data privacy”, the list goes on. Does it matter to you? Should it?

The answer to that question is for you to decide. And it likely depends on what your role is. Do you farm? Do you advise farmers? Do you sell inputs or crop protection? Insurance? Futures?

Of all the new technologies appearing on the farm, “remote sensing” systems (devices that measure conditions from a distance, commonly an aircraft or satellite) are unique in their ability to deliver information on the existing conditions in the field. And that’s valuable, because that data can be used to help decide on today’s treatments and to better predict long term crop performance.

This is the first in a multi-part series which examines how remote sensing systems can deliver value for agriculture, and how different types of systems are suited to different applications, so you can decide if remote sensing data might be valuable to you.

What do we mean by “data value”?

Before we dive into any deeper discussion, let’s first be clear on what we mean by “data value”. That will help frame comparisons we’ll make among different technologies and applications.

There’s a relatively simple framework which says that the value of any data, whether remote sensing data for agriculture or any other data, comes down to:

- How actionable is the data?

- How available is the data?

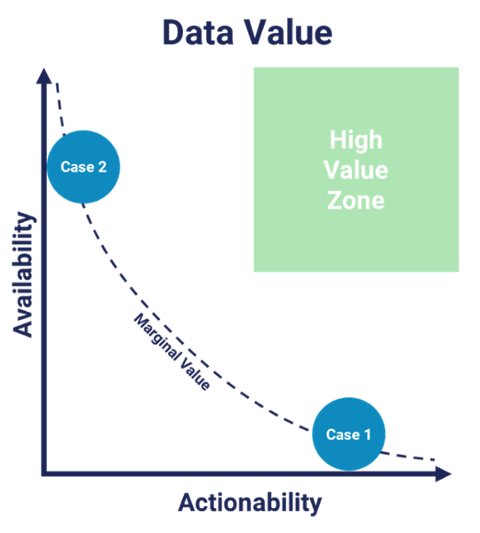

Data is “actionable” when it can be used to affect a decision. Data is “available” when it is present at the time, place, cost, and in the right format you need in order to make that decision. For data to be highly valued, it has to score highly on both tests.

Suppose a new technology is developed (call it “Case 1”) which can tell you with 100% certainty where an emergent and costly pest was affecting plants in a field, a pest for which a cost-effective treatment is readily available – that’s high actionability. Now suppose that data was not available until 2 weeks after it was collected, after the pest had already severely damaged the field – that’s low availability.

Now suppose another technology (“Case 2”) could instantly supply aerial imagery of a field whenever it was requested (high availability), but was known to contain errors such that you couldn’t trust what it’s telling you (low actionability).

We’ve captured these two cases graphically on the chart. Note that both Case 1 and Case 2 lie along a line of “marginal value”. Solutions that fall below or to the left of this line wouldn’t be worth your investment, while solutions in the upper right (labeled the “high value zone”) should be pursued –within the context of your budget and specific needs.

Whatever the data source or type, you can use this simple framework to evaluate alternatives. The important point is to consider both data actionability AND data availability when evaluating new data sources for your farming operation.

The value of different data sources

Let’s apply this framework to a more specific question – the relative value of different sources of data on the farm.

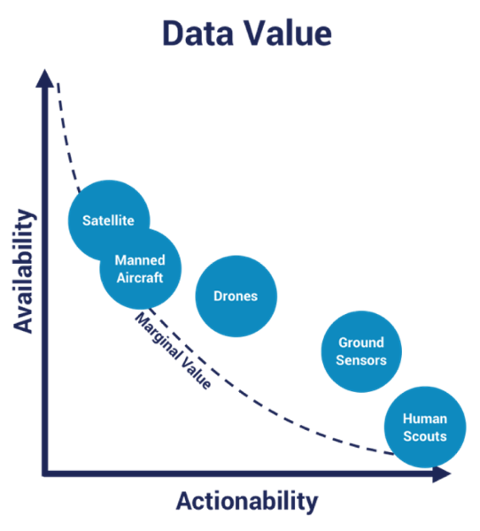

Until recently, human scouting was the only method to obtain any data on field conditions. Over the past decade or more however, satellites, manned aircraft, drones, and ground sensors have emerged as alternatives to deliver new data types aimed at improving farming practices – data to drive precision agriculture.

Each of these data sources has its advantages and disadvantages with regard to any specific farming problem but for the sake of illustrative discussion, let’s assume we’re trying to determine the nutrient status of a corn field early in the development cycle.

Human Scouts

Scouts rate highest on the actionability scale. Currently there’s no alternative which surpasses human expertise for diagnosing conditions in the field, but scouts score lowest on the availability scale because they’re sparse – they can’t realistically evaluate every acre in a field, let alone every plant.

Ground Sensors

Ground sensors can extract more accurate and precise measurements than scouts on variables such as soil moisture content or pH, however they tend to be specialized for a narrow range of applications, so overall actionability is a bit less than the scout. Because they can be deployed in larger numbers across a field and can deliver data 24/7, their availability is a bit higher than the scout.

Overhead Sensors – Satellites, Manned Aircraft, and Drones

Overhead sensing systems offer the ability to view a field in totality – so every acre can be measured efficiently.

In most cases these systems are trying to measure how much sunlight is absorbed by the plant canopy (another way of saying they measure plant color), because that data can be used to infer what types of pigments are present in individual leaves, which is a good indicator for general nutrient condition. This is a complex measurement however, which is subject to errors. In many cases, these errors are not adequately corrected so the data actionability is lower than would be expected. Uncorrected data errors contribute to misdiagnosed conditions and costly misapplication of treatment, so it’s critically important to understand these limitations, a topic we’ll address later in this series.

Going one step further, some overhead remote sensing systems (drones) can measure the shapes and sizes of individual plants to extract additional, and often more highly actionable data that simple plant color measurements won’t reveal.

Cost and ease-of-accessibility are important factors around data availability. Satellite and manned aircraft data cover large areas at reasonably low cost but are commonly impacted by weather conditions, and data delivery may lag your specific needs so availability is limited. Drone systems have far lower area coverage rates but can be deployed virtually anywhere at any time, provided they aren’t tethered to cloud-based computing requirements, so their availability is similar.

From this introductory discussion on data value, you can see that the differences among alternative remote sensing technologies are extensive and complex. In Part II of this series, we’ll examine this topic in more detail and discuss how one of the options is uniquely positioned to move “up and to the right” in the data value space over the next few years. Ultimately, this discussion is intended to help you decide which approach may best serve your needs.

The content & opinions in this article are the author’s and do not necessarily represent the views of AgriTechTomorrow

Comments (0)

This post does not have any comments. Be the first to leave a comment below.

Featured Product